Connectivity across BRICS countries

How to cite this document

Contents on this page are extracted from: “Belli L. and Magalhães L. (Eds). SmartBRICS: How the BRICS Countries are Regulating their Digital Transformation. Springer-Nature. (2025)”.

Specific country data citations should include reference to their respective chapter and authorship, as follows:

Magalhães, Larissa. Connectivity landscape in Brazil.

Orlova, Anna; Schcherbovich, Andrey. Connectivity Landscape in Russia.

Parsheera, Smriti. Connectivity Landscape in India.

Ikeng, Lin. Connectivity Landscape in China.

Hadzic, Senka. Connectivity Landscape in South Africa.

How to cite

this document

Context

1. What is the state of Internet access in the country, in terms of: a. number of subscribers across different categories; b. affordability of services; c. type of technology being used; d. gender gap; e. urban-rural gap?

Please cite as “Magalhães L. Connectivity Landscape in Brazil. In Belli L. and Magalhães L. (Eds). SmartBRICS: How Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa Are Shaping Their Digital Transformation into Smart Countries. (2023).

According to the Survey on the Use of Technologies of Information and Communication in Brazilian Households (Cetic.br, 2021) of the Regional Center for Studies for the Development of the Information Society (2020), in 2020, internet access reached 83%, representing around 61.8 million households with some type of connection.

The database on internet access in the country, referring to the year 2020, indicates that 69% of households have fixed broadband. However, the cost of the connection continues to be a barrier to home access, as 28% of residents consider the connection expensive, and 20% do not know how to use the internet. Furthermore, despite the recorded increase in access to the network, the concentration is in 50% of urban households and 100% of the richest classes.

Regarding the regional distribution of households of Internet users, access is greater than 80% in all regions. In the Southeast region the proportion of access is 82%, in the Northeast it is 80%, in the Midwest it is 87%.

Therefore, the use of ICTs in the Brazilian territory is quite heterogeneous, whose greatest disparities are between macro-regions and rural and urban areas. At the same time, the rapid urbanization of the population poses enormous challenges, especially with regard to network access infrastructure, regulations, resources and institutions in the context of climate change, the struggle for housing and a lack of basic public services[1]. This context impacts the use of networks and information technologies (ICT) and the ways of accessing services, types of technology, skills and use.

[1] The United Nations 2030 Agenda encourages countries to invest in inclusive and sustainable cities, reinforcing interventions by digital technologies.

A. Number of subscribers across different categories

According to data from the 2020 survey (Cetic.br, 2021), there was diversification between the technologies used to access the network.

The proportion of households with fixed broadband increased to 695, making it the main type of connection. At the same time, there has been a reduction in mobile broadband between 209 and 2020 to 22%. Probable reflection of social distancing and isolation policies due to the Covid 19 pandemic.

In general terms, regarding the type of broadband connection technology in households, around 56% have a cable or fiber optic connection, DSL connections correspond to 5%, satellite 5% and radio 3%. This convergence scenario reflects that 91% of internet provider companies in the country offer fiber optics.

Despite the trend of access inequalities in Brazil, differences of access in households with broadband have reduced among households with lower income. Despite the observed growth of 70% for households with income between 4 minimum wages, and 52% for households with up to 2 minimum wages.

Considering the Brazilian regions, there was also a reduction in the difference in the proportions of home access to the network, mainly between the Northeast and Southeast. The proportion of households connected in the Northeast region is 79% and in the Southeast region is 86%.

B. Affordability of services

Regarding the characteristics of internet access in households, there is a high proportion of households with WiFi reaching 85%. Among mobile internet users, 75% used the mobile network (3G and 4G), 90% used Wi-Fi and 66% used both technologies. However, the relational pattern between areas and classes remains, with 70% of low-income households having WiFi, while 100% of high-income households use the technology. Comparing urban and rural areas, only 69% of rural areas have WiFi, while 87% of households in urban areas are covered.

The presence of WiFi is lower in households whose main connection is mobile. This finding is associated with the value of data packets. Approximately 51% of households pay more than R$80 reais for the connection. This value is also symbolic for the most vulnerable households in terms of income 68% and location, with 66% being in the rural area.

C. Type of technology being used

The type of device used to access the internet is related to economy class in the first place. It is also related to infrastructure in the territorial organization of the country.

The 2020 household survey indicates that 58% of users exclusively use their cell phones to access the network. Being that 40 million people and 38 million people are from class C and DE. This classification is related to the number of minimum flights, that is, family income, so class E corresponds to the range of up to 2 minimum flights, D corresponds to the range between 2 to 4 minimum flights, class C corresponds to the range between 4 to 10 minimum flights . At the same time, 41% of users use both cell phones and computers.

In addition to the devices used to access the Internet, approximately 97% of users access the Internet at home. Regarding access devices, there was a significant increase in the use of a television set to access the Internet, among approximately 44% of network users. This growth is linked to the pandemic period, when the level of access can be compared to access via computer, including desktop, notebook or tablet. Among other devices, approximately 30% of users access via notebook, 26% via desktop computer, and 8% access via tablet, while 10% of users use video games to connect to the internet.

D. Gender gap

According to the proportion of women Internet users, there has been a growth of 12% from 2019 to 2020, with 85% accessing the Internet, while 77% of users are men. However, other issues related to structuring and sociocultural factors impact on the way women access.

E. Urban-rural gap

Although the permanence of historically structured inequalities between rural and urban areas has been observed, between 2019 and 2020, the proportion of users increased from 53% to 70% in the rural area. While in urban areas the growth went from 77% to 83%.

Please cite hereafter as “Orlova, A.; Schcherbovich, A. Connectivity Landscape in Russia. In Belli L. and Magalhães L. (Eds). SmartBRICS: How Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa Are Shaping Their Digital Transformation into Smart Countries. (2023).

Russia represents a significant part of the global Internet, with advanced connectivity infrastructure and high penetration of access among its population, conditioning active online civil society. According to Statista, Russia is today (Kemp, 2020) the 8th country with the highest number of internet users, 116.4 million (Statista, 2022), which makes it the 8th country with the highest number of internet users among the largest countries of the world.

In 2016 Russia, along with other 3 BRICS countries, was among the largest in the world in terms of the size of their digital economy, with eGDP[1] share of 28% (Cheng, 2017). Of the 10 countries with the highest eGDP share four places were taken up by BRICS countries, putting the BRICS countries in the forefront of global digital competition.

In 2018 it was 80.9%[2] of individuals were using the internet in Russia, according to the World Bank (2022). This number corresponds to the data of the Federal Service of State Statistics, in 2018 the share of individuals using the Internet in the population aged 15-72 stood at 81%. (Abdrakhmanova et al., 2020).

Fixed broadband

Fixed broadband is widespread and is rapidly expanding. In the 2016 State of Broadband report by ITU (International Telecommunications Union [ITU], 2016), Russia ranked 55th among 187 nations in the fixed broadband category, with 18.77 subscriptions per 100 inhabitants. The Federal Statistics service estimated that 66.8% of households had access to broadband at 256 kbps or more.

A. Number of subscribers across different categories

Internet penetration per age

According to the All-Russian omnibus of GfK, by the beginning of 2019 the audience of Internet users in Russia among the population 16+ made 90 million people (+3 million people by last year) and reached a point of 75.4% of the adult population of the country.

In 2018, according to the Omnibus GFK survey (Omnibus-GFK Rus, 2018) Internet penetration among young people (age 16-29 years old) is 99%, and middle-aged (age 30-54 years old) is 88% people is close to the limit values, and the growth of the Internet audience is happening mainly due to older people (55+ years old) that is 36%.

By frequency: Daily, weekly, monthly

According to NGO Public Opinion Foundation (2020) conducted between May 15 to May 17 2020 about Internet usage, 69% of russians say that they used Internet in the last day, 4% — in the last week, 1% — in the last month, 1% – in the last three months, 1% — in the last half a year, 2% — more than a year ago and 22% never used the Internet. The numbers of this research closely match data from 2018 Russian Federation official Internet access rate of 80% total (published by ITU-D).

By category: Residential, business, academic

Among the Internet users, the big majority use mobile Internet, while 60% have Internet at home. 27% use only the mobile Internet, and 21%, only at home (Tadviser, 2022).

In 2019, 44.3% of important infrastructure facilities declared having connectivity to broadband access to the Internet, according to statistics on the national project “Digital Economy” published by Rosstat.

Schools, universities, state agencies, territorial electoral commissions, medical and obstetrical centers, points of firefighters and police have support by the national program “Digital Economy”, which until 2021, has available 72 billion rubles to connect about 100 thousand facilities.

B. Affordability of services

The average monthly account on the subscriber (ARPU) is 359 RUB (5 USD), according to TMT consulting. In 2019 operators adjusted rates, considering increase in the VAT, from 18% to 20%, and also the regulatory requirements causing additional expenses – such, for example, as the Yarovaya Law, which added many requirements related to vigilance and counter-terrorism (Federal Law No. 374-FZ of July 6, 2016), requiring multimillion rublos of investments.

The cost of broadband Internet has been falling continuously in Russia. In March 2016, average monthly cost of fixed broadband subscription was 404 roubles (~$6.3) in Russia (Public Opinion Foundation, 2020), ranging from 624 to 359 ($9.8 to $5.6). Considering the monthly average salary of just over 32 thousand roubles (~$500) in January 2016, and the minimum wage of $109 set in July 2016, the cost of broadband largely meets the globally recognized affordability targets. Moreover, for residents of small villages and towns, the Russian government intends to provide subsidized subscription plans that cost only 70 US cents per month, for 10 mbit/s connection.

The cost of mobile broadband access in Russia

According to a 2019 study by analytical agency Content Review (2018), the cheapest unlimited mobile is Internet in Russia, in the rating of the cost of 1 Gb, Russia took 4th place, having improved its performance compared to 2018.

Highlights:

- the average world cost of 1 gigabyte of mobile Internet was 195.5 rubles, in Russia – 37.9 rubles (269.3 and 55.5 rubles in December 2018, respectively)

- the average world cost of a tariff with unlimited mobile Internet was 2791.8 (37.05 USD) rubles per month;

- Russia took first place in the ranking of countries[3] with the cheapest unlimited Internet;

- Russia entered the top five countries with the cheapest mobile Internet, moving to 4th place the following factors affect the cost of a gigabyte: an increase in mobile traffic packages with a simultaneous decrease in their cost, introduction of unlimited tariffs; volatility of national currencies; market competition; country size; 5G availability.

C. Type of technology being used

73 million of Russians with age of 16+ (61% of the total adult population) use the Internet on mobile devices – tablets or smartphones. 59% use the Internet on smartphones and 14% use the Internet on tablets. (Omnibus GFK survey 2018). And 32 million Russians (16+ years old) use the Internet only on mobile devices (smartphones or tablets) – this is 35% of all Internet users. However, growth of the audience in itself on the Internet is not the main news. As of January 15, 2019, within the last few years the growth of the Internet’s audience has been slowly and is generally due to the users of the senior generation connecting to the network. At the same time among youth and people of middle age penetration of the Internet is close to its limit.

D. Gender gap

In the period from July to September 2016, according to the Web Index Report, the monthly Internet audience included 85.6 million people, or 70% of Russians aged 12+. In line with global trends, younger age groups have been reached almost completely. For both male and female groups between 12-24, the percentage of Internet users ranges from 95% to 98%, and 92-93% for groups 25-34. The older groups have lower usage rates, declining to 18% for females 65+ and 29% for males 65+.

E. Urban-rural gap

With most of its population living in cities, Russia has the highest penetration of Internet among the CIS countries.Nevertheless high penetration rates in the urban areas, there are wide discrepancies in penetration among different regions and republics of the Russian Federation. In large cities of Russia, the penetration has almost exhausted its growth potential by 2015, with several million individuals still remaining unconnected in cities with less than 500 000 inhabitants and in rural areas (Yandex, 2016).

There are notable differences between small town Russia (<100,000 residents) and big town Russia (100,000+ residents), with the former having a monthly reach of 76%, and the latter only 63%. Within big town Russia, the largest cities Moscow and Saint-Petersburg stand out with higher percentages. Income group distribution also shows major differences, with 85% of self-reported income group “above average” using the Internet, as opposed to only 48% in the group “lower than average” (Digital Report, 2018).

[1] eGDP (Gross Domestic Product) is an indicator proposed by the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) that calculates digital/internet-related expenditure in private consumption, investment, government expenditure and net export.

[2] In % of population

[3] Corresponding tariffs are present in 26 out of 50 countries considered in the study.

Please cite hereafter as “Parsheera, S. Connectivity Landscape in India. In Belli L. and Magalhães L. (Eds). SmartBRICS: How Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa Are Shaping Their Digital Transformation into Smart Countries. (2023).

- Number of subscribers across different categories

India has the second largest Internet user base in the world. As per data released by the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI), there were 718.74 million Internet subscribers at the end of 2019 (Telecom Regulatory Authority of India [TRAI], 2019b) and that figure had gone up to 836.86 million by June, 2022 (TRAI, 2022). These Internet subscription figures indicate the total number of subscriptions and not the actual number of unique and active Internet users in the country. A study by the Internet and Mobile Association of India (IAMAI) and Nielsen (2019) placed this figure of active users to be in the range of about 504 million. This is about 70 per cent of the total subscriptions reported by TRAI around that period. It is also important to note that even though there has been a significant increase in the Internet subscription and usage figures in the last few years, India still sees a vast digital divide. This divide became all the more evident due to the inescapable push towards digital services during the COVID-19 crisis.

In a population of 1.35 billion, an active use base of 504 million implies that only about 37 percent of the population is actively using the Internet. This may be due to a number of supply and demand side factors. The supply side factors include affordability and availability of Internet access services and devices that can be used to connect to the Internet. On the other hand, the demand side variables include various economic, socio-cultural and demographic factors, such as income, gender, education, language, and age (Parsheera, 2019a).

The IAMAI-Nielsen study found that the highest proportion of Internet users are in the age group of 20-29 years followed by the next age bracket of 30-39 years. Notably, Internet use among the population over 50 years of age was much lower than all the other groups, which is indicative of old age being one of the barriers to Internet access.

Age-wise number of active Internet users | ||

Age group | Number of users (millions) | Per cent |

5-11 years | 71 | 14.08 |

12-15 years | 60.62 | 12.02 |

16-19 years | 73.61 | 14.60 |

20-29 years | 147.22 | 29.21 |

30- 39 years | 86.6 | 17.18 |

40-49 years | 38.97 | 7.73 |

50+ years | 25.98 | 5.15 |

Total | 504 | 100 |

Source: IAMAI-Nielsen, Digital in India Report 2019 – Round 2

The level of access also varies across different regions of the country. For the purposes of administration of telecommunications services, the country has been divided into 22 telecom service areas. While the capital region of Delhi has a very high Internet density of 198 per cent (number of subscriptions for every hundred people in the population), there are other areas like Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir, and Assam where the Internet density is much lower, being in the range of 35 to 45 per cent (TRAI, 2022). Further details of the rural-urban variations in the subscriber density are discussed subsequently.

Moreover, variations in Internet access are also shaped by the socio-economic class of users. The IAMAI-Nielsen study used the New Consumer Classification System, which classifies households based on the level of education and ownership of various consumer durables, to assess the role of socio-economic factors in Internet access. They found that 57 per cent of the Internet users belonged to categories A and B of the classification, which signified that they were the wealthier households with higher education levels. This proportion was even higher in the urban areas where 71 percent of the users fell in these two segments. However, they also found that many of the new users who were coming online, particularly from small towns and rural areas belonged to the C, D and E classifications, which indicates a broad-basing of the user profile.

Finally, the data shows that even among those who have Internet access, there are differences in the nature and extent of use. While 77 per cent of urban users reported that they used the Internet everyday, this was only 61 per cent in case of rural consumers. In fact, 13 per cent of rural users noted that they used the Internet less than once a week. In terms of activities for which the Internet was being used, the highest number of users reported chatting and social networking followed by entertainment, online news and email.

- Affordability of services

India is known to have the lowest cost of wireless Internet access in the world. As per a comparative assessment of mobile data plans from across the globe, the average price of one gigabyte (GB) of mobile data in India was UD$ 0.09, while the global average rate was about US$ 5 (Cable.co.uk, 2020). The chart below shows the comparative mobile data price in India and the other BRICS countries.

Cost of mobile data in BRICS countries | ||

Country | Average price/ GB (Local currency) | Average price/ GB (US $) |

Brazil | BRL 5.64 | 1.01 |

Russia | RUB 38.33 | 0.52 |

India | INR 6.66 | 0.09 |

China | CNY 4.30 | 0.61 |

South Africa | ZAR 101.91 | 7.19 |

Source: cable.co.uk, 2020

Affordability of Internet access is, however, shaped not only by the cost of the service but also the affordability of the device that is to be used for accessing the Internet. The GSMA’s Mobile gender gap report found that the highest percentage of the survey respondents from India reported handset cost to be one of the important barriers to mobile ownership and mobile internet use (GSMA, 2022).

As per a 2019 study, the compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of mobile phone sales volume in India between 2007 to 2018 was 6.66 per cent. During the same period the average selling price of phones decreased only by a CAGR of 0.11 per cent. The study also notes that despite the gradual increase in adoption of smartphones, the Indian market still remains dominated by feature phones, which constitute over 50 per cent of the sales volume (Kathuria et al., 2019).

One of the notable developments in this segment has been the launch of Reliance Jio’s smart feature phones in 2017, which supports 4G services on Jio’s wireless network. Reports indicate that over 100 million units of the JioPhone had been sold by 2020 (Prabhjot, 2020). Since then, Jio has launched an affordable smartphone in collaboration with Google and the two companies have announced their plans to launch a new 5G device. However, the proliferation of such offers by dominant Internet service providers could also lead to competition concerns in the medium to long term, in addition to privacy concerns arising from the possibility of data sharing between Jio and Google.

- Type of technology being used

As in many other parts of the developing world, the Internet access market in India is propelled mainly by wireless services. About 97 per cent of the Internet subscribers in India are connected to the Internet through wireless services (TRAI, 2022). Until around the middle of 2016, most wireless users were using low-speed narrowband Internet services. However, this has come to change in light of the large scale adoption of 4G services in the last few years. At present, 95 percent of the access market consists of users of broadband services. It may be noted here that Indian regulations currently define broadband to mean download speeds of over 512 Kbps, which happens to be a lower benchmark compared to many other countries.

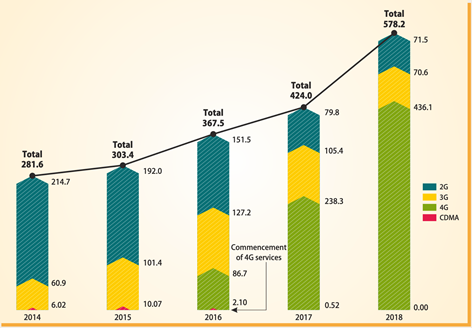

The chart below depicts how the technology-wise Internet user base in India evolved during the period from 2014 to 2018, with many users moving directly from 2G to 4G services (TRAI, 2019c). Besides the number of subscribers, the technology-wise data usage trends also point to the importance of the 4G services, which now constitute 95 per cent of the wireless internet consumption in the country (TRAI, 2022). . This goes to show that along with the steady decline in the number of narrowband users their share in the country’s total data consumption has also been decreasing.

Technology-wise trend in number of wireless subscribers

Source: TRAI Wireless Data Service Report, 2019

In case of wireline Internet access services, the total number of subscribers has increased from about 20 million in 2015 to 28.7 million by the middle of 2022. While the overall trend in this sector is not comparable to the scale of growth in the wireless Internet segment, one of the notable developments that can be seen from the chart below is the significant rise in the number of fibre connections.

Technology trends in wired Internet access | ||

Technology | Subscribers in millions (Dec, 2015) | Subscribers in millions (June 2022) |

Direct subscriber line | 13.17 | 2.79 |

Ethernet/ LAN | 2.18 | 3.58 |

Dial-up | 3.23 | 0.00 |

Fibre | 0.20 | 21.21 |

Cable modem | 1.13 | 0.94 |

Leased line | 0.06 | 0.20 |

Total | 19.97 | 28.73 |

Source: TRAI’s Performance Indicator Reports for the period ending in June 2022 and Dec 2015.

- Gender gap

As per GSMA’s Mobile Gender Gap Report, 2022, the South Asian region has a mobile gender gap of 41 per cent (GSMA, 2022). This implies that women in the region are 41 per cent less likely to use mobile Internet compared to men. In the context of India, the report notes that although the penetration of mobile internet use among women has been increasing, and saw a significant spike during the first two years of the COVID pandemic, men’s mobile internet use has increased at a greater pace. The study found that while 51 per cent of men used mobile Internet services, this figure was just 30 per cent for women, indicating a mobile gender gap of 41 per cent.

Mobile Internet use and ownership in India | |||

Type | Male population % | Female population (%) | Gender gap (%) |

Mobile owners | 83 | 71 | 14 |

Internet users | 51 | 30 | 41 |

Source: GSMA Mobile Gender Gap Report, 2022

Further, as shown in the chart above, there was also a gender gap of 14 percent in terms of mobile ownership (down from 20 per cent in 2020). The phone ownership status of men and women also varies by type of device, with 49 per cent of males but only 26 per cent of females owning a smartphone. The type of device has a bearing on whether and the extent to which one can engage with the Internet.

Researchers have noted that this mobile gender gap is driven by a mix of economic factors and normative barriers arising from social norms, customs, and perceived gender roles (Barboni et al., 2018). While the Internet gender gap in India still remains stark, it is encouraging to note that this gap has been narrowing over time — it has narrowed down from 68 per cent in 2017 to the current figure of 41 per cent.

E. Urban-rural gap

Approximately 65 per cent of India’s population lives in rural areas. However, at present, only about 40 percent of the total number of Internet subscribers in India come from rural areas. Further, the Internet density figures show that there are only 37.8 rural Internet subscribers per hundred people in rural areas, as compared to 103.2 in case of urban subscribers (TRAI, 2022). This shows that much of the adoption of Internet services has been concentrated in the urban areas. A comparison with the rural subscription figures a few years back, however, shows that there is a trend of increased adoption in rural areas although the pace of growth in the urban segment has undeniably been much higher. For instance, at the end of 2015, India had only 112.16 million rural subscribers as opposed to the current figure of 339.3 million.

There are also significant inter-regional differences in the rural and urban Internet density figures. For instance, the north-eastern state of Assam has an urban density of 115 per cent but a rural density of just 33 per cent. A similarly wide gap is also seen in other states including Bihar, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan. On the other hand, there are smaller states and regions like Goa, Sikkim and Delhi that reflect a high rural as well as urban Internet density (TRAI, 2022).

Please cite hereafter as “Ikeng, L. Connectivity Landscape in China. In Belli L. and Magalhães L. (Eds). SmartBRICS: How Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa Are Shaping Their Digital Transformation into Smart Countries. (2023).

A. Number of subscribers across different categories

Until March 2020, Internet users in China had amounted to 904 million with an Internet access rate of 64.5%; 75.08 million new users added since June 2019, contributing to a 4.9% rise in the Internet access rate.[1] Comparedly, as per the the 47th China Statistical Report on Internet Development (also applying to some latest data in the following), the number of Internet users in China reached 989 million by December 2020, an increase of 85.4 million compared to March 2020, and the penetration rate reached 70.4%, an increase of 5.9 percentage points compared to March 2020 (Cyberspace Administration of China [CAC], 2021b).

Likewise, by March 2020, cellular network users had amounted to 847 million, 29.84 million more than in 2019. However, cell phone Internet users in China reached 986 million in December 2020, up 88.85 million from March 2020. Cell phones accounted for 99.7% of Internet users.

As of December 2020, the size of China’s non-Internet users was 416 million, a decrease of 80.73 million from March 2020. Regionally, China’s non-Internet users were still mainly in rural areas, and the proportion of non-Internet users in rural areas was 62.7%, which was 23.3 percentage points higher than the proportion of the national rural population. Comparedly, the number of non-Internet users in China was 496 million until March 2020, 40.2% of those were from urban areas and 59.8% were from rural areas; 51.6% of non-Internet users don’t use Internet due to the lack of knowledge of computers and the Internet, 19.5% lack input methods (Pin-Yin), 13.4% of them don’t have access to devices such as computers, 14.0% is due to age (too young or too old), 8.8% feel the usage is unnecessary or uninterested, 7.3% report they don’t have the time for it. The previous report on the same issue in 2019 stated that 44.6 of non-Internet users don’t use Internet due to the lack of knowledge on computers and Internet, 36.8% lacks input methods (Pin-Yin), 15.3% of them don’t have devices such as computers, 14.2% is due to age (too young or too old), 10.6% feel the usage is unnecessary or uninterested, 9.4 % report they don’t have the time for it, and 5.4% don’t have access to Internet locally. In comparison to the data published in 2019, most categories in the 2020 report don’t seem to change much except in 2019 there was a category of “not having access to Internet locally”, which seemingly was added to the category of lack of knowledge to computers and Internet in 2020.

B. Affordability of services

China is actively promoting Internet access with Policies on Facilitating Faster and More Affordable Internet Connection. The Premier of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, Li Keqiang, stated on May 28th 2020 that the average annual income in China is 30000 RMB (approximately 4200 USD), and 600 million live on an annual income of 12000 RMB (approximately 1686 USD).

C. Type of technology being used

Until December 2018, users of fiber to the home (FTTH/O) in China amounted to 368 million households, taking up 90.4% of broadband Internet connection users.

Until March 2020, 99.3% of network users in China accessed the Internet via cell phones, having a 0.7% growth in comparison to December 2018; 42.7% of network users accessed the Internet via desktop computers, dropping 48% in December 2018; 35% of network users accessed the Internet via laptop computers, a 0.8% decrease compared to December 2018; 29% of Internet users accessed the Internet via tablet computers, a slight regression of 0.8% compared to December 2018; 32% of network users accessed the Internet via TV, a one percent increase to that of December 2018.

D. Gender gap

As of December 2020, the ratio of male to female Internet users in China was 51.0:49.0, which was basically consistent with the ratio of male to female in the overall population. Until March 2020, 51.9% of the users are men while 48.1% are women, also until June 202, 52.7% of the users are men while 47.3% are women, quite similar to 52.4 % versus 47.6% ratio in December 2018.

E. Urban-rural gap

As of December 2020, the number of rural Internet users in China was 309 million, accounting for 31.3% of all Internet users, up 54.71 million from March 2020; the number of urban Internet users was 680 million, accounting for 68.7% of all Internet users, up 30.69 million from March 2020. The number of urban Internet users was 680 million, accounting for 68.7% of the total number of Internet users, an increase of 30.69 million compared with March 2020. Until March 2020, rural areas contributed 28.2% (255 million) of Internet users, while 71.8 % (649 million) are from urban areas, in comparison to June 2019 when rural areas contributed 26.3% (225 million) of Internet users, while 73.7% (630 million) from urban areas.

[1] The COVID19 pandemic did result in a 50% surge of Internet traffic in China, and over 60 % rise in Wuhan, according to the Information and Communication Development Department of Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. However, it doesn’t seem to contribute to the expanding of Internet access, which has been maintaining a 2% to 4% growth each year.

Please cite hereafter as “Hadzic, S. Connectivity Landscape in South Africa. In Belli L. and Magalhães L. (Eds). SmartBRICS: How Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa Are Shaping Their Digital Transformation into Smart Countries. (2023).

This section is based on data from Research ICT Africa’s report ‘State of ICTs in South Africa’(Gillwald et al., 2018) and the policy brief ‘After Access 2022: Internet usage trends in South Africa ’(Research ICT Africa, 2022).

A. Number of subscribers across different categories

The share of South Africans using the Internet increased from 49% in 2018 to 76% in 2022. Education and income are the major determinants of mobile and Internet connectivity and use.The main barriers to Internet access are a lack of awareness and knowledge of how to use it. For those who are already online, the main barrier to using the Internet more is overwhelmingly the high cost of data.

The real gap is a poverty gap. The socially and economically marginalised are unable to harness the Internet to enhance their social and economic well-being. Despite mobile

broadband, the digital divide between the poor and the rich is significant in South Africa.

According to ITU data from 2017, 2.84% of the population uses fixed broadband, while there are 58.62% active mobile broadband subscriptions.

B. affordability of services

According to the UN Broadband Commission, affordability of data prices is defined as the price of 1 GB of data having to be less than 2% of disposable income (Alliance for Affordable Internet, 2018). In South Africa, due to the large inequalities and disparities in disposable income, some studies have shown that in 2016 in rural low income areas certain populations spent as much as 22% of their disposable income only to be able to make a few short phone calls and send some SMSes (Rey-Moreno et al., 2016).

The affordability divide between the low-income and high-income South Africans is creating barriers to connecting the low-income earners. RIA’s African mobile pricing or RAMP project tracks the cheapest baskets of 1GB of prepaid data in several African countries. In the last quarter of 2012 the cheapest pack of 1GB data in South Africa was was around 4.65 USD. (Research ICT Africa, n.d.)

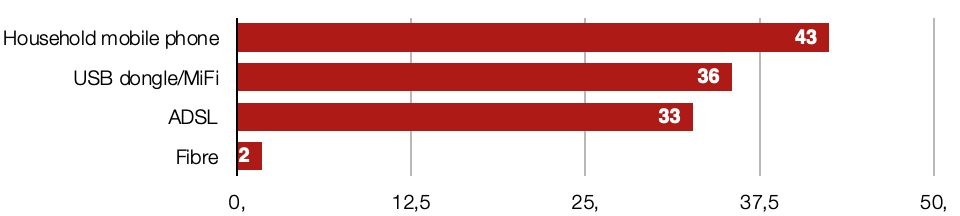

C. Type of technology being used

During the After Access Survey (household and individual user survey, analyzing the demand side) in 2017, 62% of households reported one or more members having access to or using the Internet. However, most of this access (57%) takes place ‘using mobile devices’, with just over 10% of households reporting Internet access ‘at home’.

Mobile devices, such as USB dongles, portable hotspots and mobile phones are the primary tools that are used by those households that do access the Internet, while fibre is only used by 2% of the population.

One of the reasons why mobile wireless technology is dominant is the availability of data services that can be purchased incrementally at low cost, such as top-up on demand – instead of committing to a prescribed monthly fee.

Source: ‘State of ICTs in South Africa’, Research ICT Africa

D. Gender gap

While the GDP per capita figure masks extreme inequalities in South Africa, the country performs well in relation to gender equity. The gender gap in Internet use in South Africa was 12% in 2017. Since then until 2022, it has become almost neligible.

In contrast to other African countries, where all ICT indicators favour males, in South Africa females (85%) are more likely to own a mobile phone than men (83%). However, males are more likely to own a smartphone than females. This suggests that men are more likely to be able to afford more expensive phones and that most women are unable to buy smartphones due to income disparities. This, in turn, would imply that females are less likely to access the Internet.

E. Urban-rural gap

While the gender gap seems to be fading, disparities in access still exist between urban and rural populations. However over the period between 2018 and 2022, the rural gap decreased from 22% to 10%.

2. What is the country’s ranking in the global ICT indices, such as ITU’s ICT Development Index (IDI), WEF’s Network Readiness Index (NRI), A4AI’s Affordability Drivers Index, GSMA’s Mobile Connectivity Index (MCI)

A. Classification on the ITU ICT Development Index

After the release of the 2017 index (International Telecommunication Union [ITU], 2017), there were some recommendations for modifying the indicators to increase the accuracy of the assessment of the development of information and communication technologies in the countries.

However, the quality of the data for evaluation in 2018, with the recommended changes already, pointed out significant flaws in the set of indicators, so the index was not released. The most recent indicator (ITU, 2019) was also based on the original methodology, since the data obtained from the changes contained problems, even after the orientation workshops.

Therefore, the International Telecommunication Union maintained the indicators and published the 2019 index. Brazil is classified as a developing country.

B. The classification in the WEF Network Preparation Index

The Network Readiness Index 2022 (Dutta & Lanvin, 2022) assessed a total of 131 economies and the multifaceted impact of information and communication technologies on society and the development of countries. Considering the overall scores, there are no major differences between the top ranked countries. Brazil occupies the 44th place. On the pillars, in technology the ranking is 43, people is 40, governance is 44, and impact is in position 61.

C. A4AI Accessibility Driver Index classification

The index assesses the political, regulatory and supply environment for internet access, with the aim of providing more accessible broadband. The index classifies countries according to the expansion capacity of the technology infrastructure deployed, the local political structure for equitable access and the adoption of broadband.

According to the 2022 ranking (Alliance for Affordable Internet [A4AI], 2022), Brazil occupies the 15th position, with a score of 72.89 for access, and 59,09 for infrastructure. However, Brazil dropped some positions in the ranking because of delays in the implementation of rules of law and permission on tower zoning.

D. The classification in the GSMA Mobile Connectivity Index

The most recent connectivity index is from 2022. Brazil has a score of 62.51, there are more specific relevant scores: 99% have 3G coverage, mobile connection has 106% penetration, and mobile broadband connections have 102% penetration.. The infrastructure score is 74.8, with an emphasis on network coverage of 89.5, however, with a performance of 76,4. The affordability index is 59.4, the inequality is 10, handset price 62.3, taxation 73.6, and the mobile tariffs of 80. Regarding the consumer profile, readiness is 80, basic skills 67.6, mobile ownership 78.8, and gender equality 93.2. Finally, the content and service index are 87.3, with an emphasis on the low online security index of 57.5.

The connectivity index confirms the gaps in internet access in Brazil, accentuated by the low accessibility and quality of the infrastructure, mainly due to the high cost and lack of digital skills, and low investment in local exchange points.

A. Classification on the ITU ICT Development Index

In ITU’s ICT Development Index Russia’s IDI 2017 rank is 45, with the IDI 2017 value 7.07; (no ranks were issued in 2018 and 2019).

B. The classification in the WEF Network Preparation Index

In 2019 Russia’s NRI rank is 48 with a score of 54.98, with an upper-middle income. The group of Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) is headed by Russian Federation (48th). Its best performance relates to People (38th), especially the ICT usage and skills of firms and national authorities (35th in Businesses and 32nd in Governments). At the level of the subpillar, meanwhile, the country does even better when it comes to Inclusion (29th). However, the same pillar — Governance (56th) — also includes Russian Federation’s weakest dimension in the NRI: Regulation (91st). Other areas in need of improvement include Future Technologies (72nd) in the Technology (51st) pillar and Quality of Life (85th) in the Impact pillar (59th). The associated pillars, Technology and Governance, are also the two weakest dimensions of the CIS, which suggests that many countries in the region should pay more attention to promoting online safety and ICT regulation and to preparing themselves for disruptive technologies like artificial intelligence and Internet of Things.

C. A4AI Accessibility Driver Index classification

Russia has not been ranked in A4AI’s index.

D. The classification in the GSMA Mobile Connectivity Index

Russia’s score for the GSMA’s Mobile Connectivity Index for 2018 is 73.0 (the Difference 2014-2018 score is 6.9). The category with the highest rank was consumer readiness, earning 86.6 points (with basic skills scoring 84.0 and gender equality 88.2). The infrastructure in mobile connectivity, which included network coverage and performance among other criteria, was the weakest sector with a score of 64.6 The content and service sector has the score of 75.9.

Ranking in global ICT indexes | ||

Index | Rank | Observations |

ITU’s ICT Development Index, 2017 | 134 of 176 | The index consists of three sub components. India scores were as follows: Access sub-index — 3.60 Use sub-index — 1.62 Skills sub-index — 4.73 The ITU has not published a revised version of the index since them although work is in this direction is reportedly in progress |

Network Readiness Index, 2021 | 61 of 131 | India received a score of 51.19 on the index. The index consists of four pillars, across which India received the following scores: Technology — 48.8 Impact — 55 People — 50.9 Governance — 50.9 This index was previously released by the World Economic Forum. However, since 2019, this is being led by the Portulans Institute (PI). |

A4AI’s Affordability Drivers Index, 2021 | 10 out of 72 | India received a score of 72.32 out of 100 on this index. Its scores on the communications infrastructure and access sub-indexes were as follows: Communications infrastructure — 60.8 (rank 12) Access sub-index — 75.5 (rank 13) Affordability index – 72.3 (rank 10) |

GSMA’s Mobile Connectivity Index, 2022 | 94 of 170 | India received a score of 61.3on the index, which consists of the following sub-components: Infrastructure — 59 Affordability — 69 Consumer readiness — 47 Content and services — 74 |

In 2017, China’s IDI ranked 80th worldwide with the value of 5.60 (global average being 5,11), and is one of the fastest growing countries. (International Telecommunication Union [ITU], 2017) China ranked 59 in the WEF’s Network Readiness Index (NRI) with a value of 4.2 (Portulans Institute, 2022) while ranking 35 out of 61 countries in A4AI’s Affordability Drivers Index with the value of 52.25 out of 100 (Alliance for Affordable Internet [A4AI], 2021). China scored 74.3 in the GSMA’s Mobile Connectivity Index, scoring 73.9, 67.3, 76.3, 80.2 in infrastructure, affordability, consumer readiness and content and services respectively (GSMA, n. d.).

The ICT Development Index (IDI) is a composite indicator launched by ITU in 2009 to assess and benchmark the developments in information and communication technology (ICT) across countries and over time. In the last edition from 2017, South Africa ranked 92nd globally (Research ICT Africa, n.d.), out of 176 assessed countries (data from 2017) with the IDI value 4.96.

Since then, ITU launched a process for revision of the indicators included in the IDI, and a new version of the IDI (ITU, 2020) will be published soon.

WEFs Network Readiness Index (NRI) focuses on international competitiveness.

In the 2021 evaluation, South Africa was ranked 70th out of 130 countries (Portulans Institute, 2022) , with the overall score 48.88. Again, the score on ‘governance’ (which includes regulation) was relatively high – 61.25, however due to the low uptake (the score on ‘people’ and ‘impact’ was 46.42 and 42.25, respectively) the overall rank dropped significantly. The ‘technology’ score was 45.59.

A4AIs Affordability Drivers Index (The Affordability Report 2021) looks more at affordability, and out of 72 countries that were evaluated in 2021, South Africa was 27th. SA scored 68.51 on the access sub-index, 49.50 on the infrastructure sub-index, and 62.58 on the affordability driver index (where it climbed up one rank since the last evaluation).

GSMA’s Mobile Connectivity Index (GSMA 2021) looks at mobile Internet uptake.

South Africa scored 64.5 in the 2021 evaluation of the index, scoring 65, 53.9, 74.0, 67.0 in infrastructure, affordability, consumer readiness and content and services, respectively.

The infrastructure index calculation is based on network coverage (90.8), network performance (60.4), other enabling infrastructure (67.4) and spectrum (30.7). Obviously, the fact that South Africa has failed to release high demand spectrum contributes to the low overall infrastructure index. Favourable taxation (85.4) does not compensate for extremely high levels of income inequality (0.0) and high mobile tariffs, hence the affordability index is the weakest of all four components. The affordability index is additionally composed of handset price (47.9) and mobile tariffs (74.7). The consumer readiness index is calculated based on mobile ownership (75.5), basic skills (61.9) and gender equality (85.4). Content and services index calculation is based on local relevance (64.6), availability (63.6) and online security (78.5).

Essentially, in terms of these indices, South Africa generally ranks somewhere in the middle globally, but in the African context often significantly ahead of other African states.

3. Does the country have a strategy for the expansion of Internet access, such as a national broadband plan or similar?

The National Telecommunications Agency (Anatel) updated the Structural Tactical Plan for Telecommunications Networks (PERT). The 2019-2020 Plan was designed with the objective of expanding access to broadband in Brazil, with adequate quality and prices, through the coordination of efforts and investments, between the public and private sectors, therefore it is a regulatory and formulation input of public policies that establish infrastructure goals for the implementation of networks essential to public services[1].

The Structural Plan for Telecommunications Networks (PERT) focuses on structural deficiencies in the transport and access networks that support the provision of broadband services. In addition to diagnosing the telecommunications infrastructure, the document focuses on deficiencies in the access and transport network that support broadband services[2]. With the diagnosis of broadband, the agency establishes priorities, guiding and coordinating the telecommunications sector. PERT is also linked to the 2015-2024 Strategic Plan, which seeks to promote consumer satisfaction, competence and sustainability in the sector, dissemination of data and information from the sector, emphasizing access, use, quality and performance of services as the main commitment. Among the tactical guidelines of the agency’s strategy, the following stand out: expansion of transport and access infrastructure; satisfaction, quality and price by improving consumer relations; stimulating sustainability and competition among service providers; promoting the efficient use of the spectrum and regulatory performance for a responsive model; institutional strengthening.

Among the programs of the agency’s strategic plan and the Union’s 2020-2023 Pluriannual Plan, the “Conecta Brasil” program aims to promote access by expanding broadband from 74.68% to 91.00% through regionalized targets[3]. Decree nº 9.612 of 201 established the promotion of access to telecommunications considering the economic conditions of services; such as expanding broadband access in underserved, rural or remote urban areas; and digital inclusion to guarantee access to technologies in areas characterized by social inequalities.

Other specific measures are part of the 2025 Program, Communications for Development, Inclusion and Democracy – under the responsibility of the Ministry of Science, Technology, Innovations and Communications (MCTIC). The program’s goals are: to increase the average speed of fixed broadband, to increase the proportion of access to mobile broadband to 90%, to make mobile broadband available in all municipalities, and to expand the coverage with an optical transport network (backhaul)[4].

[1] PERT is part of Anatel’s Tactical Plan 2019-2024, established through ordinance 2,382 / 2019 (Agência Nacional de Telecomunicações [ANATEL], 2020b)

[2] Telecommunications networks are divided into: core, transport and access. The access network is the local network that connects the user to the operator’s network. The transport network (backhaul) is the intermediate section of the network, which connects this local network to the central network (backbone) of the provider, from which interconnection with other national and international providers takes place, enabling access to the internet.

[3] Information about Conecta Brasil and the Pluriannual Plan available at the Ministry of Communication’s official webiste (2021b).

[4] For more information about the 2025 Program, see the document released by the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management (2020).

Russia’s strategy for Internet access expansion along with other technological development aspects is broadly outlined in the following set of documents and frameworks on Russia’s vision for the national broadband development and digital economy:

- National program “Russia Digital Economy Program” outlining Russia’s goals for 2025;

- May 2018 Presidential Decree;

- State program of the Russian Federation “Information Society (2011-2020)”;

- the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) Agenda 2025.

Also, until 2018 Russia had a national broadband plan that had very ambitious goals for mobile broadband coverage expansion. The aforementioned documents and agendas serve as a logical continuation of the previous national broadband plan.

There is a Decree of the President of the Russian Federation from May 7, 2018 on national goals and strategic objectives of the development of the Russian Federation for the period until 2024 (Decree of the President of the Russian Federation No. 204 of May 7, 2018). This law prescribes to the Government of the Russian Federation to ensure the accelerated introduction of digital technologies in the economy and social sphere among other national development goals of the Russian Federation for the period until 2024.

In accordance with this law the roadmap “The main activities of the Government of the Russian Federation for the period until 2024” (2018) was approved by the Government on September 27, 2018. This is the key document of strategic planning of the Government of Russia until 2024.

In the section 2.1. on “Digital Economy of the Russian Federation” of the aforementioned document, the Government of the Russian Federation is aimed to achieve the following goal and targets of the national project “Digital Economy of the Russian Federation” in regards to the national broadband plan:

“creation of a stable and secure information and telecommunication infrastructure for high-speed transmission, processing and storage of large amounts of data, accessible to all organizations and households, including providing broadband access to the information and telecommunication network “Internet” of households and socially significant infrastructure objects, the creation of reference data centers in federal districts, an increase in the share of the Russian Federation in the global volume of provision of data storage and processing services”.it

Investment into a globally competitive secure infrastructure to support the growth of a data driven economy remains (The World Bank, 2018) a top priority, as emphasized in the May 2018 Presidential Decree.

In July 2017, Russia adopted the Russia Digital Economy Program with an expected annual budget of US$1.8 billion until 2025 (Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation No. 1632-r of July 28, 2017) to address the current weaknesses preventing the country from joining global digital economy leaders.

To manage the program, five basic directions for the development of the digital economy in Russia for the period until 2024 have been identified. The basic directions include normative regulation, personnel and education, the formation of research competencies and technical background, information infrastructure and information security.

The Digital Economy national programme adopted by Government Order 1632-p of July 28 2017 sets the provision of stable 5G mobile services in all major cities of Russia by 2024 as one of its major goals.

The Digital India mission is a flagship programme of the Indian government. It includes a number of initiatives which have been brought under nine key pillars that include the creation of broadband highways, securing mobile connectivity for all and the creation of public Internet access (Digital India, n. d.). One of the components of the broadband highways mission is the Bharat Net project for the creation of a national optical fibre network. The project aims to provide broadband connectivity to 250,000 village Panchayats, or village level local governance institutions. A government undertaking called Bharat Broadband Network Limited has been created to manage the roll out of the Bharat Net project. Once this infrastructure has been created, all service providers will be allowed non-discriminatory access to it to launch services in rural areas.

The implementation of the project has been much slower than anticipated. The project is now in its second phase and as of November 2022 only 188,243 of the 250,000 village Panchayats had been declared to be service ready (Bharat Broadband Network Limited, 2022). The reasons given by the government for the delay in the project include delays in commencement due to field surveys and pilot testing of the technology, right of way issues and delays being caused at the state government level in the latest phase of the project (Government of India, 2020).

The National Digital Communications Policy (NDCP) announced by the Department of Communications (DoT) in 2018 also recognises the provisioning of broadband access for all as one of its strategic objectives (Department of Telecommunications, 2018a). It articulates that the following mission is to be achieved by the year 2022 — To promote Broadband for All as a tool for socio-economic development, while ensuring service quality and environmental sustainability.

Some of the specific goals that have been laid down in the policy include universal broadband connectivity for all citizens at 50 Mbps, 1 Gbps connectivity to all Gram Panchayats, enabling 100 Mbps broadband on demand to all key development institutions, including all educational institutions, and deployment of public Wi-Fi Hotspots to reach 10 million people by 2022. In terms of institutional mechanisms, the NDCP speaks of the creation of a National Broadband Mission that will implement the rural connectivity and public Wi-Fi initiatives as well as a Fibre First Initiative to focus on fibre to the home development in Tier I, II and III towns and rural clusters.

In May 2020, Cyberspace Administration of China, National Development and Reform Commission, State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of the People’s Republic China jointly issued the 2020 working plan of poverty alleviation through internet services. (Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), 2020) The working plan aims to improve internet and broadcasting infrastructure in rural and poor areas; through projects like Extending Radio and TV Broadcasting Coverage to Every Village Project (National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Finance & General Administration of Radio, Film and Television, n.d.) (村村通, the literal translation is connection between villages, the project isn’t limited to radio and TV broadcasting coverage) as well as nationwide trials of providing universal telecommunication service, rural areas and poor areas in China started to enjoy the convenience of Internet and information society. Until October 2019, fiber optic network and 4G network has over 98% coverage in administrative villages, while poor villages have a 99% broadband coverage. In 2013, China issued the “Broadband China” strategy and Implementation Plan, the plan has five main goals: to promote regional broadband development, to accelerate the optimization and upgrade of broadband networks, to improve the application of broadband networks, to promote the development of broadband industry chain, and improve the capacity of maintaining broadband network security. Take promoting regional broadband networks development as an example, the goal was divided into three different sectors, eastern, central and western, and rural farm areas. For the eastern part of China, the goal is to actively utilize optical fiber and new generation of mobile telecom technology as well as TV broadcasting technology to improve the performance of broadband networks, ultimately catching up with developed countries. Central and western areas focus on broadband networks infrastructures, improve the capacity of backbone networks and inter-network interconnection capabilities, and broadening the coverage of broadband networks. As for rural farm areas, the goal is to take broadband into the coverage of universal telecommunication services, and further enforce the Extending Radio and TV Broadcasting Coverage to Every Village Project mentioned above; different technologies such as fiber optic, copper wire, coaxial cable, 3G/LTE, microwave, satellite transmissions have been adopted to speed up the expansion of broadband networks in administrative areas and natural villages. (The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China, 2013)

Broadband expansion has been prioritized in the National Development Plan. Government adopted a national broadband policy in a document entitled ‘SA Connect: Creating Opportunities, Ensuring Inclusion’ (Electronic Communications Act, 2005).

The four central strategies adopted in the policy are

- Digital readiness

- Digital development

- Building the digital future

- Realising digital opportunity

The strategy is designed to provide universal accessibility across the country at a cost and quality that meets the needs of citizens, business and the public sector, as well as access to the creation and consumption of a wide range of converged applications and services required for effective economic and social participation.

The SA Connect document contains several targets expressed as ‘broadband access in Mbps user experience’. The targets also differentiate between targets for the population as a whole and targets for schools, health facilities and government facilities.

Essentially the targets are as follows:

Target | Penetration measure | Baseline (2013) | By 2016 | By 2020 | By 2030 |

Broadband access in Mbps user experience | % of population | 33.7% internet access | 50% at 5 Mbps | · 90% at 5 Mbps · 50% at 100 Mbps | · 100% at 10 Mbps · 80% at 100 Mbps |

Schools | % of schools | 25% connected | 50% at 10 Mbps | · 100% at 10 Mbps · 80% at 100 Mbps | · 100% at 1 Gbps |

Health Facilities | % of health facilities | 13% connected | 50% at 10 Mbps | · 100% at 10 Mbps · 80% at 100 Mbps | · 100% at 1 Gbps |

Government Facilities | % of government offices |

| 50% at 5 Mbps | · 100% at 10 Mbps

| · 100% at 100 Mbps |

However the strategy failed to meet 2016 targets as well as 2020 targets.

Besides SA Connect, the other main policy initiative was the protracted National Integrated ICT Policy White Paper, which was finalized in 2016 and accepted by Cabinet and Parliament. It focuses on improving access to infrastructure, competition (particularly in the services market), and inclusion of all citizens in the digital economy. The white paper covers everything from revised institutional arrangements for the sector to universal access and service and cybersecurity. (National Integrated ICT Policy White Paper, 2016)

International Commitments

1. Is the country a member of the ITU?

The ITU is the United Nations System Agency dedicated to topics related to Telecommunications and Information and Communication Technologies. The entity supports the shared global use of the radio frequency spectrum, through the international cooperation of orbital satellites, the improvement of the telecommunications infrastructure, establishes standards for interconnection between various communication systems, and is committed to topics such as climate change, accessibility and strengthening security cybernetics. The agency operates in three sectors: standardization of telecommunications, radiocommunications and the development of telecommunications. Brazil has been a signatory of international technical cooperation projects with the ITU since August 1877. The headquarters of the Americas regional office is in Brasilia.

Yes, Russia, the Russian Empire at the time, joined the ITU (International Telegraph Union) in 1865 (1865/12/31), and since then, the Russian Federation has been a member of the ITU, which since 1934, is named International Telecommunication Union.

India has been a member of ITU since January 1, 1869 and has been a regular member of the ITU Council since 1952. It was last re-elected to the Council in 2018 for a 4-year term from 2019 to 2022 (Press Information Bureau, 2018a). At present, there are 20 ITU members from India, which includes government organisations, service providers, academic institutions and other entities. The Department of Telecommunications (DoT) is the nodal agency for coordinating with ITU from India.

In September 2018, ITU announced the establishment of an ITU South Asia Area Office and Technology Innovation Centre in New Delhi. Besides India, this office will serve eight other countries in the region, namely, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Iran, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka (Press Information Bureau, 2018b).

Yes. South Africa became a member of the ITU in 1881. In 1965 following the Montreux Plenipotentiary Conference South Africa was excluded from participating in meetings of the Organisation but continued to remain a member of the organisation. A follow-up decision taken at the 1989 Plenipotentiary Conference in Nice resolved that South Africa would continue to be excluded from all conferences, meetings and activities of the ITU until such time as apartheid policies were eliminated. This resolution was set aside by the Executive Council on 9 May 1994 and formally adopted during the 1994 Plenipotentiary Conference.

South Africa submitted instruments of accession to the constitution, convention and optional protocol of the ITU on 30 June 1994, thus permitting its full participation in the ITU with effect from the 1994 Plenipotentiary Conference held in Japan. At that conference and at the subsequent conferences in Minneapolis, in 1998 and Marrakech, in 2002, South Africa was nominated and elected to membership of the Council. (PATU/ATU, 2004)

In 2018, South Africa was elected (South African Government, 2018) into the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) Executive Council and Radio Regulations Board (RRB).

Before the establishment of the Department for Communications and Digital Technologies (DCDT) in 2019, the Department of Communications (DoC) was responsible for setting electronic communications policy, overseeing radio frequency spectrum and representing South Africa in international fora such as the International Telecommunications Union (ITU).

2. Is the country a signatory of the 1988 or 2012 version of the International Telecommunication Regulations (ITRs)?

Yes. The International Telecommunication Regulations (ITRs) are global treaties applied to establish the principles of supply and operation of international telecommunications, facilitating interconnection and interoperability through networks and services. In 1988, the World Conference on International Telecommunications updated the regulations; in 2012, the rules on international tariffs were prioritized.

Yes, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) signed the 1988 ITRs. Russia has signed the 2012 ITRs.

India is a signatory to the International Telecommunication Regulations (ITR) of 1988. It, however, did not sign the 2012 version of the ITRs adopted at the World Conference on International Telecommunications in Dubai (Masnick, 2012).

China is a signatory of the 2012 version of the ITR.

Yes. South Africa signed (ITU, 2004) the 2012 version of the International Telecommunications Regulations.

3. Does the country have a policy of following ITU recommendations or/and technical standards?

The ITU has played a crucial role in Brazil since the privatization and modernization of telecommunications, following the Anatel, which is the regulatory body and the Ministry of Science, Technology, Innovation and Communications. ITU and Brazil have cooperation projects aimed at the development of telecommunications, such as support and integration of indigenous communities, children and young people in the information society.

Article 69. on “International cooperation of the Russian Federation in the field of communications” of the Federal Law of 07.07.2003 No. 126-FZ (The law “On Communications”) defines the policy of working with ITU:

“The Communications Administration of the Russian Federation, within the limits of its authority, represents and protects the interests of the Russian Federation in the field of telecommunications and postal services, interacts with communications administrations of foreign states, intergovernmental and international non-governmental communications organizations, and also coordinates the issues of international cooperation in the field of communications carried out by the Russian Federation, by citizens of the Russian Federation and Russian organizations, ensures the fulfilment of obligations of the Russian Federation arising from international treaties of the Russian Federation in the field of communications.”

“Telecommunications Administration” (administration) is the government agency or service responsible for fulfilling obligations under the Charter of the International Telecommunication Union, the Convention of the International Telecommunication Union and the Radio Regulations. In Russian Federation, the Ministry of Digital Development, Communications and Mass Media (until 2018 the Ministry of Telecom and Mass Communications of the Russian Federation (Minsvyaz) acts as a Telecommunications administration.

The Unified License agreement through which the Government of India authorises a telecom operator to carry out telecommunications services in the country contains certain references to the ITU’s standards. It requires that the licensee can only use such equipment or products that meet the standards specified by the DoT’s Telecom Engineering Centre (TEC). Where no such mandatory standards have been laid down by TEC, the licensee can only use those equipment and products that meet the relevant standards set by recognised International standardization bodies, including the ITU (Department of Telecommunications, 2016b).

The TEC’s standardisation guide sets out the process for ratifying/ adopting national standards in India based on the standards developed by the Telecommunications Standards Development Society, India (TSDSI) or international standards transposed by them. The TSDSI is an autonomous, multi-stakeholder body that is recognised by the DoT as India’s National Telecom Standards Development Organisation (Department of Telecommunications, 2018c). It carries out standards development for telecom and information communication technology (ICT) products and services in India (Telecommunications Standards Development Society, India [TSDSI], 2022b). The examples of international standards listed in the guide include those published by bodies such as the Organisation for International Standardisation (ISO), International Electro-technical Commission (IEC) and the ITU.

As per a presentation made by the Executive Director of TSDSI in 2016, some examples of ITU standards based products in India include the telephony signaling protocols, Signaling System No. 7, the integrated services digital network (ISDN), Gigabit-capable passive optical networks (GPON) and Intelligent Networks (Chauhan, 2016).

Yes, most of China’s telecommunications related legislation and regulations is in accordance with ITU standards, for example the Measures for the Management of Filing, Coordination, Registration and Maintenance of Satellite Networks Article 1 states: In order to strengthen and standardize the declaration, coordination, registration and maintenance of satellite networks, these Measures are formulated in accordance with the “Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Radio Management” and the regulations of the International Telecommunication Union (hereinafter referred to as ITU) (Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, 2017b). The Technical Requirements for the Average Loudness and True-Peak Audio Level of Digital Television Programmes of China also follows ITU Recommendation BS.1864-0 (03/2010). (The State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio and Television, 2014)

South Africa supports various ITU initiatives (Cwele, 2018);

- Since 2015, South Africa has been serving as an active member of the UN Broadband Council for Sustainable development under the leadership of ITU and UNESCO Secretary Generals.

- South Africa has been actively participating in various ITU committees and regional meetings.

- In 2018, the ITU Telecoms World Conference was hosted in Durban, South Africa.

- As a legacy of this conference and with the support of ITU and other international organisations, the African Digital Transformation Centre was launched in the capital city of Pretoria. This Centre’s objective is to incubate enterprise talent, harness innovation and prepare the African continent to take full advantage of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. It will assist African Small, Medium and Micro Enterprises (SMMEs) with conformance testing, standardisation and protection of their intellectual property. It will contribute to the development and utilisation of African-produced ICT solutions designed to meet local needs.

The Independent Communications Authority of South Africa’s mandate (ICASA, n.d.) is to regulate the telecommunications, broadcast and postal services in the public interest and ensure affordable services of a high quality for all South Africans.

In regulating the industry ICASA aligns its actions, policies and regulations with frameworks set by international and regional bodies to which it is affiliated, including the ITU.

Although overall high-level spectrum policy and international country interaction with the ITU are clearly under the Ministry’s domain, regulatory practice in many jurisdictions with independent sector regulators (or spectrum agencies) leaves spectrum management and band planning within the ambit of such a specialised agency, along with regulation, assignment, licensing, charging, monitoring and enforcement in relation to spectrum.

4. What is the composition of the country’s delegations at ITU meetings, including official reunions and study groups (e.g. government only, or multistakeholder including private sector, academia and civil society representatives)?

The Brazilian composition is multi-sectorial and made up of governmental bodies and entities, private entities and the academic sector. The National Telecommunications Agency is the administrative and regulatory body and is supported by the Ministry of Science, Technology, Innovation and Communications. The delegation of associated consultants is represented by Advisia OC&C, and telecommunications operator Claro SA, as a SIO, Idea Eletronic System, Multiedgers, and SBA Communication.. The academic sector is represented by the CPqD Foundation – Center for Research and Development in Telecommunications and the Federal University of Pará, in addition to the Regional Office of the ITU in Brasília.

The composition of Russia’s official delegations at ITU meetings consists of: government, private sector (namely state (co)-owned companies) and academia (state universities).

Only one delegation representing the Administration of Communications of the Russian Federation may be sent to an international ITU event.

The composition of Russia’s delegations at ITU’s meetings, in particular to the Plenipotentiary Conference of ITU, world and regional conferences and assemblies, is defined by the Ministry of Information Technologies and Communications (Order of the Ministry of the Information Technologies and Communications of the Russian Federation No. 47 of December 29, 2004). The Russian Federal Communications Agency (Rossvyaz) is responsible for the formation of the delegation in cases where an international procedure for coordinating the use of radio-frequency assignments, including orbital-frequency positions for spacecraft, is carried out.

As the technical wing of DoT, the TEC represents it in international bodies like the ITU (Telecom Engineering Centre, 2017). In addition, it is also possible for individuals from other organisations like the TSDSI, industry and academia to be a part of the delegation (Biswas, 2017). For instance, the TSDSI provides an online form through which one can solicit information for participating in ITU-T’s study groups 13, 5, 17 and 20 (TSDSI, 2022a).

Further, the DoT has also constituted National Working Groups on ITU’s study groups to contribute to the ITU’s activities keeping in view the interests of India’s telecommunications sector (Telecom Engineering Centre, 2017). The role of these working groups is to build consensus and harmonise the interests of various stakeholders and proactively make contributions to ITU’s relevant study group meetings (Telecom Engineering Centre, 2022).

The delegation of China at ITU meetings is composed of Bureau of Radio Regulation of the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (the State Radio Office), the State Radio Monitoring Center, the State Radio Spectrum Management Center, the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology, National Radio and Television Administration, Bureau of Telecommunications Regulation of Macau, Office of the Communications Authority of Hong Kong, related telecom corporations, satellite operators and manufacturers (Industrial Culture Development Center of the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, 2019).

The composition of South Africa’s official delegations at ITU meetings (ITU 2022) consists of: government, private sector (both state (co)-owned companies and fully private) and academia (state universities).

The administrative body is the Department of Communications and Digital Technologies, with the support of Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (ICASA) and Ministry of Communications and Digital Technologies.

The private sector is represented by three major operators (Telkom, Vodacom and MTN), Sentech (signal distributor for the South African broadcasting sector), and engineering companies GEW Technologies and Orbicom.

The academic sector is represented by the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR).

5. Is the country a member of the WTO? If so, is the country a signatory of the general agreement on trade in services?

In 2016, Brazil implemented its commitment to the WTO through the acceptance of the protocol on financial services. The country has acceded to the Fifth Protocol to the General Agreement on Trade in Services of the WTO (GATS) (World Trade Organisation, 2016).

The Russian Federation has been a member of WTO since 22 August 2012. As part of WTO accession, Russia signed the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) that provides a legal framework for addressing barriers affecting trade in professional services.

Yes, India has been a member of the WTO since 1 January 1995. It has also been a signatory to the General Agreement on Trade in Services since its entry into force in 1995. India has listed specific requirements relating to the telecommunications sector in its Schedule of Specific Commitments. The requirements relating to this sector have been indicated in the original Schedule of Specific Commitments dated 15 April 1994 and were later updated on 11 April 1997 (GATS/SC/42, 1994; GATS/SC/42/Suppl.3, 1997).