Why the rest of the world should be worried, and think hard about how to create a data protection culture.

By Luca Belli

In Brazil, like in most all low-income countries with relevant population, enormous personal databases are created with little or very poor attention paid to cybersecurity and data protection concerns. On 20 January, the largest personal data leakage in Brazilian history was discovered. While there is no official register of data leaks in Brazil, it is difficult to think that a wider and more detailed set of data about the entire population can be leaked let alone even exist.

The massive data sets were initially spotted by PSafe, a cybersecurity start-up, on a Dark Web forum and subsequently reported by Tecnoblog, a Brazilian tech portal. The databases available – either for free or for sale – include names, unique tax identifiers, facial images, addresses, phone numbers, email, credit score, salary and more. They exposed 223 million Brazilians. If the figure sounds odd, as the Brazilian population is only around 210 million, it is because the leaked data sets also encompass the personal data of several million deceased individuals. 104 million vehicle records are also available.

The fact that much information included in the leak is typically used by credit scoring bureaus, together with the enormous extension of the databases has led many observers to suspect the leak may have originated from Serasa Experian, the leading Brazilian credit-scoring bureau. At this stage, however, this supposition has not been confirmed by any official investigation, while Serasa denies that the leakage originated from its system.

A condensed version of the datasets is offered for free on a Darknet forum. An even more pervasive database, including 14 Gigabit of almost any thinkable information about every single Brazilian individual, enterprise and vehicle is currently on sale.

The free version includes “only” full name, unique tax identifier, called “CPF”, date of birth and gender of all 223.74 million individuals. The Brazilian tech portal reported that the link to download the data set has even been indexed by Google Search and access to shady Dark Web areas is not even essential to find it.

Those interested in the complete package must spend between $ 0.075 and $ 1 per individual. The amount depends on the quantity of data you are interested in purchasing. The more you buy the better the discount you can get. Data are sold in packages starting at $ 500 and payments can be executed in Bitcoin only.

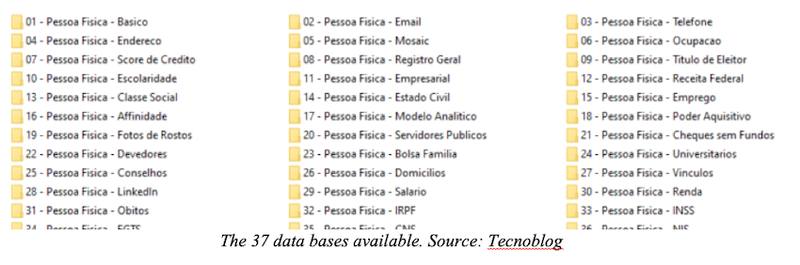

The 37 bases on sale include literally all types of personal data you may think of, plus many you are not really thinking about. These include ID number, marital status, and list of all first-degree relatives (parents, son or daughter, siblings, spouse), complete home address (including latitude and longitude), credit score, voter registration number, profession, and even link to LinkedIn profile.

The free version includes “only” full name, unique tax identifier, called “CPF”, date of birth and gender of all 223.74 million individuals.

The databases also feature data that are processed typically by credit bureaus such as level of education, salary, income, purchasing power. While not confirmed, Serasa Experian came under suspicion because of the type of data and the way the data sets are organised. The fact that data are categorised in ways that allow for the identification of specific groups and segments of potential consumers is strongly reminiscent of how this company structures its targeted advertisement and customer categorisation. For instance, one of the available data sets is called “Mosaic” and includes information organised according to the Mosaic model, a Serasa Experian consumer-prospect service, classifying enterprises as “large, traditional and influential”, “small rural traders” and “young entrepreneurs on the rise”.

This is only the last sobering example of a long series of blatant data leakages, probably only comparable to the Equifax case, when personal data of 145 million people leaked from the US credit bureau. Readers around the world may wonder: How could this scale of leak happen after Brazil adopted its new General Law for the Protection of Personal Data (better known as LGPD)? Isn’t the law in force since September 2020? Yes, it is. However, as Brazilians are now discovering the hard way, having a law is just an embryonic step towards data protection.

Crucially, the lessons that Brazil now has to learn apply everywhere personal data are collected. What matters the most is how the protection of personal data is culturally integrated by people, businesses, and administrations, and how the law is enforced. It is useless to create fancy data protection laws, copying and pasting rights and obligations from foreign frameworks, if no one in your country knows such norms exist or how to properly implement and comply with them. The country may now appear on a nice map featuring nations with data protection laws (hooray!) but the situation on the ground will likely remain dramatically distant from the letter of the law.

Although data protection has been a source of debate for decades in specialist circles, it is a very new concept for most people and very few companies or organizations consider it a priority. At the same time, personal data are harvested at scale and both market and, increasingly, social practices tend to consider personal data as something that one should trade carelessly. In Brazil, in any given drugstore or supermarket, you will be asked your CPF number by the cashier, before even being asked to pay. And if you do not share this unique identifier, people will look at you surprised, considering you are bizarre person that refuses “the discount”.

Worryingly, even when organisations are aware of the existence of the new data protection law, and of the new data security obligations, they do not know how to bake privacy into their technical and organisational structures. The fact that data protection is new, means there is an incredible shortage of professionals able to properly structure compliance with the law and to diligently observe data security best practices. Most people self-proclaiming themselves “data protection specialists” on social media, probably matched in number only by “blockchain evangelists”, have started approaching the topic no longer than one or two years ago.

Having a law is just an embryonic step towards data protection.

The Brazilian government established a new Data Protection Authority by decree only at the end of August 2020, even if the norms that mandate its creation is the only part of the LGPD which is in force since December 2018. The new Authority will play a key role, but so far, it has issued no regulation as it is still in the process of being – literally – built from scratch. Only on 28 January, it published its first regulatory agenda. Guidance on how to perform audit on personal databases, particularly regarding data security is simply non-existent. And, in such context, the government has announced the upcoming creation of a new digital identity system.

Both the inadequate level of data protection and the appetite for digitalisation of everything, as fast as possible, are common features in many countries, especially low-income ones, eager to embrace technology for development reasons. This tendency has been turbocharged by the current pandemic. However, the recent Brazilian leakage underscores that serious concern with data protection can no longer be postponed. Sustainable digitalisation cannot happen without strong data protection.

To deal with it seriously, national data protection strategy is needed, starting from well-designed capacity building initiatives targeting the entire population. This is the only way to create a data protection culture, where people and organisations alike understand the value of protecting data. Not only by having well-informed consumers and citizens but also by realising that offering strong data protection is a key factor to win competition.

Only when the value of data protection is fully understood, will it be possible to embrace the idea of sustainable digitalisation.

Originally published on 3 February 2021

Source: openDemocracy